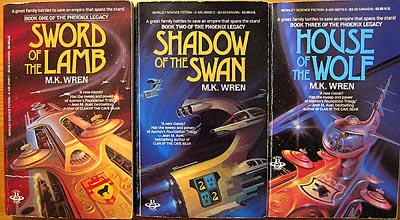

I’ve been looking for a word to describe the particular narrative flavor of MK Wren’s trilogy The Phoenix Legacy (Sword of the Lamb, Shadow of the Swan, and House of the Wolf, all first published 1981), and failed to find it, though I’m sure it exists. I’m sure there’s a dance in which the stances are as important as the movement, and in these novels, the moments of reflection are as important, if not more so, than the action that – often off-stage – precedes them.

I’ve been looking for a word to describe the particular narrative flavor of MK Wren’s trilogy The Phoenix Legacy (Sword of the Lamb, Shadow of the Swan, and House of the Wolf, all first published 1981), and failed to find it, though I’m sure it exists. I’m sure there’s a dance in which the stances are as important as the movement, and in these novels, the moments of reflection are as important, if not more so, than the action that – often off-stage – precedes them.

MK Wren has described the trilogy as an historical novel set in the future. The dominant political entity is the Concord, a neo-feudal political entity spread across multiple planets, in which a small Elite rule over the Fesh (professionals) and even more numerous Bonds (serfs). The trilogy is primarily the story of Alexand DeKoven Woolf, grandson of the Chairman of the Concord, and son and heir to one of its leading families. An educated, thoughtful young man, Alexand is unable to remain oblivious to the instability and fear that is eroding the Concord, with recurrent Bond uprisings met by increasingly brutal repression. Through his scholarly, sensitive brother, Richard, he becomes aware of the Society of the Phoenix, founded a generation ago by the leader of the defeated Peladeen Republic and a group of primarily Fesh revolutionaries dedicated to bringing about an evolution of their society. Richard, already mortally ill, is convicted of treason for his membership and submits to a martyr’s death in an attempt to offer a model of submission to the Bonds. When their father rejects Richard’s sacrifice, Alexand realizes his own political impotence as mere heir, stages his own death and assumes the identity of Commander Alex Ransom of the Phoenix’ military arm. In joining them, he offers the Phoenix an eventual entry into the Elite, provided he survives, and provided he can be restored to his former status. The remaining two books depict the working out of Alexand’s destiny, with repeated betrayals of Alexand and the Phoenix from within that lead him eventually to the same execution platform that his brother died on, years before.

The story and characters are engaging, though perhaps too black and white. The good are fundamentally good and the evil fundamentally evil. Good people may oppose each other – as Alexand’s father does Alexand – but ultimately make the right choice. Love offers salvation, for both Alexand and the assassin Bruno Hawkwood. The patriarchal, feudal society leaves too little latitude for Alexand’s brave and clear-eyed beloved, Adrien Eliseer, to act, so her part of the story is somewhat unsatisfying, though the more egalitarian Society of the Phoenix produces physician Erica Radek and young radical Val Severin. In her flaws and fallibility, Val is one of the most interesting characters: manipulated to betray Alexand, she then strives to redeem herself in her own and his eyes.

I mentioned the distinctive narrative strategy. SF novels commonly use quotes and excerpts from documents that belong to their fictional worlds, though I’ve seldom seen it done so intensively as here. There main story is interspersed with numerous interpolations of personal, historical and sociological documents, mainly as written by Richard’s various aliases, historian, sociologist and Phoenix agent. They fill in some fifteen centuries of back-story, but also introduce several key historical figures, the most important being Lionor Mankeen, who fought a failed war of liberation against the Concord, and Elor Peladeen, founder of the conquered Peladeen republic, whose stories are set against Alexand’s as alternative destinies.

And I mentioned the rhythm of the narrative as being like a mannerly dance, in which the stances are as important as the motions. Each chapter is a single scene, encompassing a relatively brief interval in time, and that moment is often as not the moment of reflection after a revelation or an action, rather than the revelation or action itself: the death of Ivanoi and his family, the death of Elise Galinin Woolfe, the capture of Andreas and Alexand, the meeting in which Adrien pleads with his father for Alexand’s life – all are described in retrospect, as the viewpoint character grapples with the emotional and political implications. We are given only a brief, intense glimpse of a terrified Rich in hiding during a Bond uprising, which proves seminal in his determination to enter the Phoenix – though a longer, first-person description is provided in the very first pages of the book, through one of the interpolated documents. The Phoenix’ brief war with the Concord is depicted entirely from the perspective of a non-combatant, Predis Ussher, traitor and usurper. Two purposes are achieved: a unity in the account, and an inside look at the destruction of the dream of conquest. It’s a distinctive approach that emphasizes interior experience over physical events. It gives the novels a romantic intensity, but also a sometimes offbalanced stillness that is certainly contrary to current fashion, and may not be to everyone’s taste. I like it, though.