(Cross-posted from Reality Skimming.)

It seemed to come together late for all concerned, but it came together: Con-Version 23. I’d decided to be a lurker at this con and not volunteer for any panels, and I headed over to Calgary a day early to have a chance to hang out with Rebecca Bradley (science GOH) and Marie Jakober. Coming in to land from the north, I didn’t get much sense of Calgary’s growth, which I am assured has been prodigious; it was certainly as green as the coast, testifying to a wet summer. No mosquitos, because of the cold, change from Westercon.

First event, after a side-trip to the UofC library to polish off a little work, was Rebecca and Robin’s party, attended by the Con GOH Jack McDevitt, the singing IFWAns (more about them later), Edge notables and assorted others such as Marie and myself. Though blurry with fatigue (How can someone get jet-lagged on a 1 h time change? – I blame the altitude) I was up until midnight, having fascinating back-deck and buffet-table conversations on a huge range of subjects, and eating too much of the yummy food. I finally got to thank Jack McDevitt for giving me my one and only Nebula award nomination, years ago, for Blueheart. Lynda Williams, Jennifer Lott (Lynda’s daughter) and Nathalie Mallet arrived from PG around 9 pm, all full of beans despite having driven all day.

The Show’s Not Over ‘Till the Captain Sings

The con itself kicked off the following evening, with the opening ceremonies, which I skived, and with the musical: “The Phantom of the Space Opera”, which I am very pleased I did not, though I arrived after the start and missed seeing the chair at the front Marie had saved for me. Stood at the back, and took digital pot-shots of the action, most of which turned out blurred. Either the subject was dancing too hard, or I was laughing too hard.

In brief, the story involves the crew of the Starship Insipid, captained by one Captain Quirk, who endure a visitation by the Phantom of Space Opera (Steve Swanson), who is searching the galaxy for musical talent. One by one, in a desperate attempt to avert the consequences of having the Captain sing, the crew take turns trying to impress the implacable Phantom. Dr. Temperence “Bones” Brennan (Rebecca, perfectly typecast) standing in for Dr. Leonard “Bones” McCoy, alas can do little for the mounting casualty count, declaring “I’m the lady who loves bones” and delegating the disposal of the inadequately skeletonized remains to Nurse Chapstick (Colleen Eggerton). Which works fine until Amanda Grayson (Danita Maslan) reveals she was standing in for her son Spork, who has returned to Vulcan on account of Ponn Farr, at which point Nurse Chapstick, who has been waiting SEVEN LONG YEARS for this, demands the keys to the space shuttle; Phantom or no Phantom, dead redshirts or no dead redshirts, she’s Vulcan-bound. Shotty (Kim Greyson) delights the audience if not the Phantom with “Pretty Kingon”, complete with lusty growl, delivered to the Klingon women on the viewscreen. The blue-collar gang receives a moment in the spotlight never granted them by the original show as the ship’s plumber and Number 2 (Val King) takes her turn at command between coffee and lunch break (got a good union, that woman), and the ship’s cook (Nicole Chaplain-Pearman) deals handily with a sudden infestation of tribbles (protein!). Even the Bored, with their multicoloured suspiciously Rubic’s cube-like ship and tinfoil prostheses, are summarily dispatched.

But the end is unavoidable – the Captain (Randy McCharles) has to sing. For a moment it seems as though the villain will be incapacitated by the sheer screechin’ sonic horror of the Captain’s highs – as indeed are all the crew and the front 5 rows of the audience – but the song ends, the Phantom rallies, and Things Look Bad for Our Heroes. Quick huddle; Captainly insight that the Phantom’s mortal weakness is that he is a male phantom, at which point Lieutenant Allura (Anna Bortolotto) is pushed forwards with urgent instructions to – well, distract him. “Can it be,” breathes the Phantom. “Can it be … talent?” While Lt. Allura hypnotizes the Phantom, Shotty and others – a little conga line – sneak up on him with the quantum technobabbleogizmo intended to neutralize his power (which looks suspiciously like a Tralthan football sock).

The Phantom bagged, he is expelled from the conveniently-located bridge airlock, and swallowed by a whale (which I know is, as Granny Weatherwax would say, Traditional, but I’m having a little bit of trouble fitting into the story). Nothing keeps a bad pandimensional being down, and the Phantom promptly reappears, and boy, is he ticked. So the story ends, very Untraditionally, in death and destruction. Or I may not have got that straight, but I was laughing too hard.

For additional entertainment, there were viewscreen interpolations of Leonard Nimoy’s rendering of The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins, and William Shatner’s Rocketman, delivered in his best lounge-lizard recitative. There was also a very strange mockumentary – I hope it was a spoof – about an attempted demolition of a beached whale carcass.

Most of the cast members have been filking and singing karaoke for years. The strength of the voices varied, but the performances were consistently lively, and the words came through well. There was a continuity hiccough in the middle where a miscue sent the entire cast 15 minutes into the future, but that was quickly corrected and, hey, this is SF! And it enabled a couple of priceless ad-libs from people who were clearly having WAY too much fun. I gather the filming didn’t take, so the cast are or have reassembled to videotape it; when they do, ooh, I wants it! My photos on Flickr:

- The cast reprises their opening number “All that Jazz” at the costume competition.

- Captain Quirk confronts his nemesis.

- Space-shake, courtesy of The Bored.

- Rebecca, in motion!

Announcing, ORU Anthology 2

Lynda’s ORU panels have become a standard feature, and this one was special because of the release of the Okal Rel Anthology 2 from Windstorm Creative, which included stories from IFWA members, and a classy cover by none other than the Phantom himself (Steve Swanson). Lynda’s copies had not arrived by the time they made it out, but Sandy Fitzpatrick’s had [link to Flickr]; I apologise for the flash whiteout of the book cover, but in the photo without flash, the book was visible, but the faces looked like they’d been cast in a horror-movie and had just seen the monster over my shoulder! Lynda distributed more of the famous ORU buttons (I picked up the ones that said “Get Rel” and “I make bad cargo” – the latter being from Righteous Anger and referring to Horth’s being a very bad backseat driver). I read the scene from Throne Price that introduces Horth, Sandy read the beginning of her story “Return”, and Randy the beginning of his, “For Amanda”.

Lynda, Marie and Rebecca Get Religion

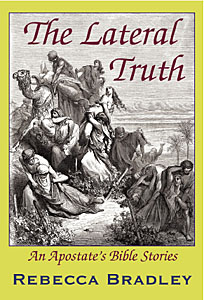

All in their different ways. On Sunday morning, Lynda and Marie did a two-woman panel on “Unconventional Religion and SF: The Way of the Future in More Ways than One?” The balance was more towards life than science fiction, with discussions of the need for ritual, whether religion is necessary as a moral anchor for a society, whether religion’s influence was benign or pernicious in the modern world, whether the human race will evolve beyond a need for religion, private versus public religion, etc. As is usual, on Monday, the day after Con-Version, the very first copies of Rebecca’s forthcoming The Lateral Truth: An Apostate’s Bible Stories arrived from Scroll Press; it is to be their second release, in November. Rebecca read two stories from it. The first I don’t recall, but the second “The Cares of the World, and Martha”, is a sardonic commentary on the tendency of male revolutionaries to take for granted that domestic comforts just happen. Marge Piercy (feminist author of Vida – about the radical left in the 60s and 70s – and City of Darkness, City of Light – about the French Revolution) would approve.

All in their different ways. On Sunday morning, Lynda and Marie did a two-woman panel on “Unconventional Religion and SF: The Way of the Future in More Ways than One?” The balance was more towards life than science fiction, with discussions of the need for ritual, whether religion is necessary as a moral anchor for a society, whether religion’s influence was benign or pernicious in the modern world, whether the human race will evolve beyond a need for religion, private versus public religion, etc. As is usual, on Monday, the day after Con-Version, the very first copies of Rebecca’s forthcoming The Lateral Truth: An Apostate’s Bible Stories arrived from Scroll Press; it is to be their second release, in November. Rebecca read two stories from it. The first I don’t recall, but the second “The Cares of the World, and Martha”, is a sardonic commentary on the tendency of male revolutionaries to take for granted that domestic comforts just happen. Marge Piercy (feminist author of Vida – about the radical left in the 60s and 70s – and City of Darkness, City of Light – about the French Revolution) would approve.

Rebecca’s several science GOH presentations stemmed from her interest in Alternative Archaeology, the heady brew of misdatings, misattribution, mysticism, charlatanism, and fantasy that swirls around antiquities such as Nan Madol, Tihuanacu, and the Sphinx. She entertainingly dissected the many and strange roots of the pseudo-science of Paleovisitology, as promulgated by von Daniken.

News and new releases

At one point I came into the Dealer’s Room to find a group-photo just breaking up: this was Edge, making the official announcement of its merger with Dragon Moon Press, which, with the previous merger with Tesseracts, makes it the largest dedicated SF/F publisher in Canada. And the ORU was there at the beginning: Throne Price was Edge’s third title. (Marie’s The Black Chalice being the first). I’d long admired the Dragon Moon covers, and I picked up a copy of Jana Oliver‘s Sojourn, partly because of its cover, and party because I was wondering how she’d manage to pull of what promised to be a merry farrago of time-travellers, shape-shifters, and historical serial killers in 1888 London. She did. It moves quickly, with details of a less-than-idea future deftly sketched in (adding a new twist to redundancy – being marooned in time), and two charming Victorian gentlemen (with secrets of their own) and an amiable large spider as companions to her independent time-travelling heroine.

Aside from The Lateral Truth, the other books I’m waiting impatiently for are Nathalie Mallet’s The Princes of the Golden Cage, which is gathering good reviews (see Nathalie’s blog), and Nina Mumteanu‘s Darwin’s Paradox, which is forthcoming from Dragon Moon Press.

SF is Alive and Well and Living in Calgary

A panel on “Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy” attested to the vitality of the Canadian SF scene: Susan Forrest from Red Deer Press, Brian from Edge, academic Robert Runte, Karl Johanson of Neo-Opsis, and writers Nina Mumteanu, Calvin Jim (aka helmsman Sudoku of the good ship Insipid) and Lynda. Virginia O’Dine from Bundoran Press was in the audience. What distinguishes Canadian SF: Robert’s take on it (maybe quoting, I didn’t note down): American SF ends with the character triumphant, Japanese SF has no ending, British SF ends in gloom and defeat, Canadian SF ends in a different place altogether, unsure whether it’s better or worse. Either I don’t agree, or I’m not Canadian, since my own resolutions could be best described as “the end of one set of problems is the beginning of another” (a steal from the end of Marge Piercy’s Gone to Soldiers, by the way), which I consider optimistic – since by then the reader should know the character’s up to it. I don’t think British SF is quite as gloomy any more: in the 70s and 80s, yes, but the space opera renaissance doesn’t encourage it. The hero-as-bystander phenomenon in Canadian SF was the subject of a thread in the SF Canada listsrv recently.

What else?

Doing karaoke with the IFWAns until long after the last bus had gone – the DJ said he’d never known a first set go 2 and a half hours. Good food: both the Radisson Airport hotel restuarant and the nearby Thai Place were excellent. Good company: eating lunch with Rebecca, Marie, and Jack McDevitt; eating breakfast with Lynda, Jenny and Marie, eating at times I’d lost track of with Marie and Jenny. Missing panels while talking about David Weber’s Bahzell fantasies with Sandy. Coming late to Jack McDevitt’s reading and being perplexed and entertained by an excerpt from his story from the forthcoming anthology “Sideways in Crime“. Talking about researching European history with Nina Mumteanu. Hanging out at the Edge table [Flickr] – come a long way from 3 books! Other things I’m sure I’ll remember once I’ve hit publish on this enormous post. I did try live-blogging via email, but found my entries parked in the ‘draft’ queue when I logged in. Time to find and change a default.

All photos on Flickr tagged with conversion23.

Con-Version 23 on Technorati: “Con-Version 23”